How Nutrition Actually Works

As the world grows more obese, we should stop treating nutrition as a black box. It starts with knowing what we eat.

Back in elementary school, my teachers would use the Food Pyramid to describe how to eat healthy. Younger readers may not be familiar with the Food Pyramid, but that might be a hidden blessing. Its recommendations were somewhat arbitrary. Throughout the years, the United States would continue to revise its dietary recommendations. However, Americans (and people in the rest of the world) continued to grow more obese.

With nutrition, our society suffers from too much instruction and not enough understanding. When we're told to "eat this" or that "this is unhealthy," it makes us outsource our thinking. What's worse is when the recommendations begin to contradict each other. Then it's outright confusing. Instead, it's better to know how your body actually interprets food. We can then derive an action plan from first principles. Most people see nutrition as a black box. You can change that.

This post contains three main sections:

A History of the Food Pyramids 📜

Nutritional Building Blocks 🧱

Actionable Eating 🥦

A History of the Food Pyramids 📜

(This entire section is a history lesson and can be skipped. If you're only interested in the fundamentals of nutrition, skip to the next section.)

For several decades, the United States government has been giving dietary advice. It's a typical case of good intentions being spoiled by bad results (and lobbyists). Let's take a look.

Food Pyramid (1992 - 2005) ⚠️

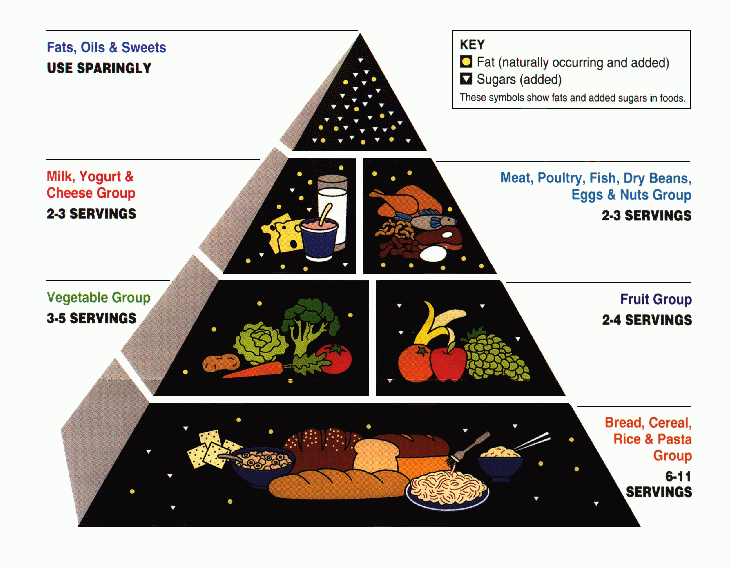

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) came out with the first iteration of the Food Pyramid back in 1992. At the time, the recommendations revolved around the concept of food groups. Specifically, there are 6 different categories:

Grains

Fruits

Vegetables

Dairy

Meats, Beans, Eggs, and Nuts

Fats, Oils and Sweets

For each food group, the USDA recommended a certain number of servings to consume per day. Grains were at the bottom of the pyramid and composed the bulk of the recommended diet. Oils and sweets lived at the top and were supposed to be consumed "sparingly."

While the Food Pyramid created a guideline about how to eat, it was rife with problems.

The food categories did not align with science.

Serving recommendations were both poorly-defined and inaccurate.

Lobbying played a crucial role in the final design.

Food Categories

I suspect the food group for grains was supposed to be a way of representing carbohydrates. But in that scenario, starchy foods such as potatoes should belong in the group.

Fruits and vegetables tend to be nutritionally similar, so there's no need for two groups. On the other hand, fats should not be in its own group, since all foods contain some amount of fat. These are some of the many grouping issues present in the Pyramid.

Serving Sizes

The concept of a "serving" isn't particularly helpful. The size of a serving can be arbitrary, meaning there's no standardized measure. Also the idea to consume fats "sparingly" can be dangerous. Humans need to consume some degree of fat, so preaching that "fat is bad" is an oversimplification. Meanwhile, having vegetarian or dairy-free diets can be perfectly fine.

Lobbying

When digging into the specifics of the Food Pyramid, observers can notice hints of lobbyist influence. For example, dairy products don't warrant their own food group. The dairy industry would think differently. (People who remember the Food Pyramid may also remember the "Got Milk?" campaign. The dairy industry has money to burn.)

It's also odd that cereal made its way into the grain group. Nutritionally, it ought to belong in the "Sweets" group. But cereal companies wouldn't be too happy if the government recommended limiting cereal intake.

It's funny in some sense. When you look at the Food Pyramid, it's split not by what's healthy. Rather, you see who paid the most to have their product shown on the menu.

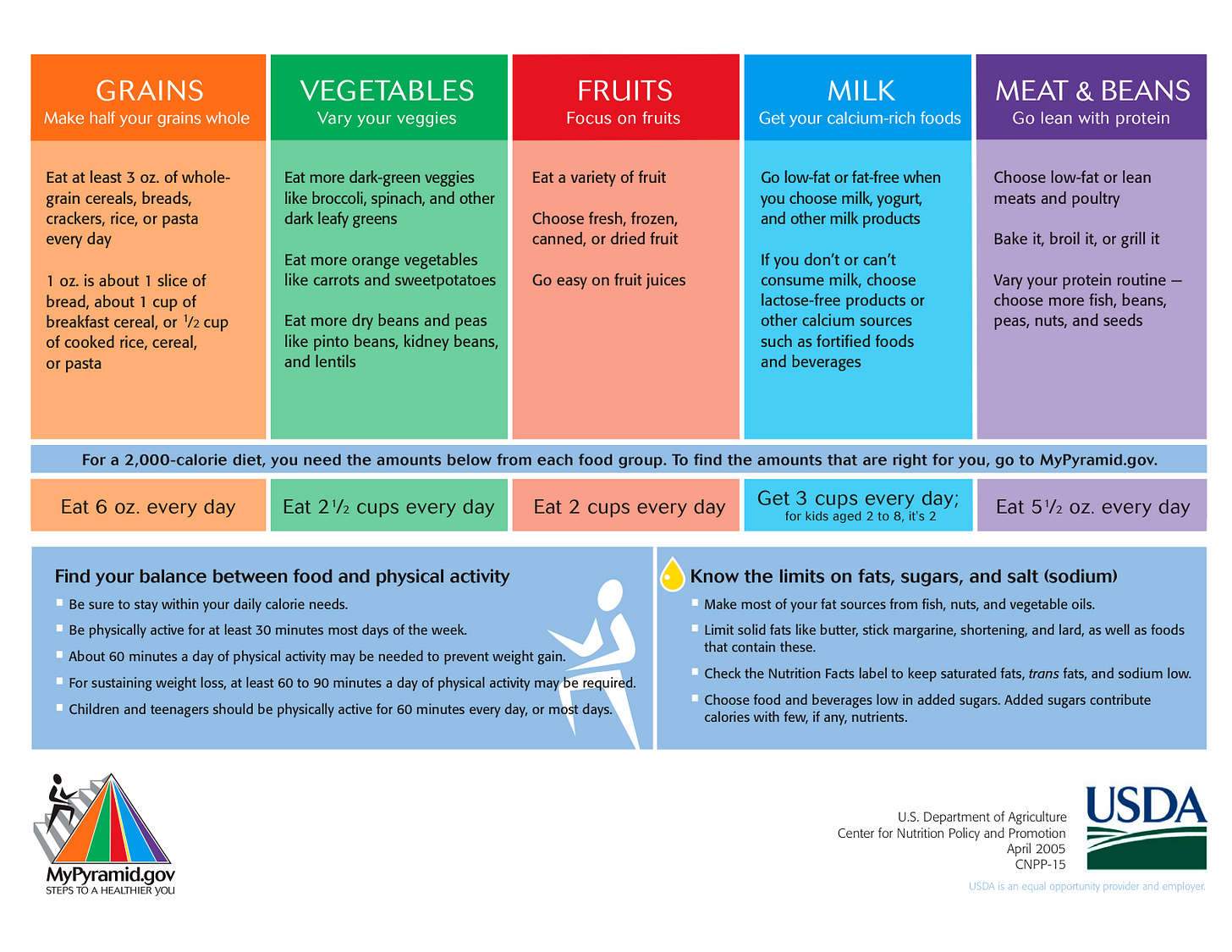

MyPyramid (2005 - 2011) 🪜

After a long decade, the USDA decided that the Food Pyramid was problematic and needed a facelift. In 2005, they replaced the Food Pyramid with MyPyramid. While MyPyramid still had problems, to its credit, it was a slight improvement. There were two notable changes:

There was a new "group" representing physical activity.

Serving sizes were replaced with legitimate measurements (e.g. cups and ounces).

Unfortunately, MyPyramid still carried the same lobbyist influences from its predecessor. The main food groups were largely the same. MyPyramid also drew criticism for being too complicated and confusing. Compared to its predecessor, MyPyramid had a short lifespan and was taken down after 6 years.

MyPlate (2011 - present) 🍽️

MyPlate replaced MyPyramid in 2011 after criticism of the latter being too confusing. It is the current USDA recommendation.

Instead of listing out food quantities, MyPlate describes the ratio of food types. Unfortunately, it suffers from oversimplification. The absolute quantity of food still matters, and the food groups still don't make sense. (Notice how dairy has stubbornly persisted across all USDA recommendations.)

To be fair to the USDA, getting nutritional guidance right isn't easy. But as long as the USDA suffers from the influence of food industries, don't expect reliable information. I don't see MyPlate lasting for too long before it's replaced by a new set of recommendations.

Nutritional Building Blocks 🧱

(This section is a bit of a chemistry lesson. If you're only interested in actionable advice or have PTSD from your high school orgo classes, skip to the next section.)

Consuming food serves two main purposes:

Provide energy for activity (and to live).

Provide materials to grow and repair the body.

Notice that physical or mental pleasure is not one of the purposes of eating. It may be one of the derived side effects, but don't confuse it with the legitimate biological purposes.

With nutrients, it's helpful to view things through the lens of chemistry. Humans digest foods into certain chemical compounds that can used in the future. These chemical compounds are known as nutrients. The body can later trigger chemical reactions using nutrients as reactants or catalysts. These chemical reactions tend to either generate energy or construct cells.

We can examine nutrients through three fundamental components:

Macronutrients 🍲

Calories 🍭

Micronutrients 💊

Macronutrients 🍲

Macronutrients comprise the chemical compounds that generate energy for the human body. These also tend to be the compounds that humans need the most. As such, macronutrients are typically measured in grams.

There are three core macronutrients:

Carbohydrates 🍞

Proteins 🍗

Fats 🥑

When the body breaks down macronutrients, it receives energy from the compounds. Residual compounds from these macronutrients may also used for other vital purposes. It's worth noting that the body cannot naturally produce most of these compounds, meaning you need to have a reasonably balanced diet to live.

Carbohydrates 🍞

Carbohydrates constitute the primary source of energy in the body. They comprise a family chemical compounds that include monosaccharides and polysaccharides. You may know these as sugars and starches. Besides energy production, the body also needs carbohydrates to support the immune system.

Carbohydrates can be divided into simple or complex carbs. Simple carbs tend to be sugars, while complex carbs can be found in foods such as brown rice or bread. The body uses simple carbs for energy, meaning simple carbs are easy to digest. It will break down complex carbs into simple carbs over time.

Proteins 🍗

Proteins are compounds made of amino acids. Besides being an energy source, the amino acids play a role in constructing the body. High sources of protein tend to be meats, eggs, and legumes.

Note that the body cannot naturally produce certain necessary amino acids. Therefore you must consume protein to live. Meats and eggs already contain all necessary amino acids. Vegans need a more varied diet (e.g. wheat and legumes) in order to cover all necessary amino acids.

Fats 🥑

Fats are compounds made up of fatty acids. Fatty acids sustain the health of cell membranes, and thus help sustain skin and hair health. Like with the other macronutrients, fats can also be used as an energy source.

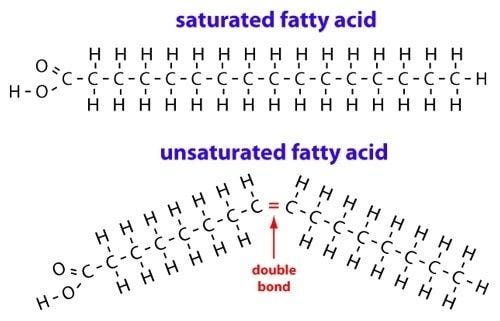

Among the fatty acids, there are subcategories based upon the molecular structure of the compounds.

Unsaturated Fat 🐟

Saturated Fat 🥩

Trans Fat 🍟

Unsaturated fats contain at least one bent double bond between its carbon atoms. In practice, it means that these compounds cannot clump together tightly. These are the "healthy" fats and are in foods like fish, nuts, and avocados.

Saturated fats replace the carbon double bonds with single bonds to hydrogen atoms. The compound thus has a shape that allows it to be packed very densely. The dense packing of saturated fats in turn allows the build-up of bad cholesterol. Enough bad cholesterol will clog your arteries. You should try to limit consumption of saturated fats.

Trans fats occur commonly in foods made with hydrogenated oil. On a molecular level, trans fats are unsaturated fats whose shape gets transformed. There are no health benefits to trans fats whatsoever. As a result, the United States banned creation of artificial trans fats in 2018. Avoid consuming trans fats if possible.

Other "Macros"

There are other nutrients whose status as a macronutrient is debatable. The core macronutrients provide energy and are necessary in large quantities. On the other hand, these three compounds do not fit both requirements:

Ethanol 🍷

Water 💧

Fiber 🥕

Humans can metabolize ethanol, also known as drinking alcohol. However, it only provides energy and no other benefits. Thus you're literally consuming "empty calories."

Water does not provide any energy. Instead it acts as a catalyst for internal human reactions. Some consider it a macronutrient since humans need a large quantity of water to survive.

Fiber is a type of carbohydrate that cannot be digested (and doesn't provide energy). Instead, it aids with digestion. Fiber can be typically found in foods with complex carbohydrates.

Calories 🍭

When you consume food, you can also think in terms of how much energy the food provides. Energy consumption and expenditure determines weight gain or loss.

Nutrition is normally measured in kilocalories. Kilocalories can also be called Calories (with a capital "C"). To remove ambiguity, I will refer to it as a kilocalorie when necessary. A kilocalorie is equivalent to 1000 calories (with a lowercase "c") and 4184 joules. A calorie represents the energy needed to raise one gram of water by one degree Celsius.

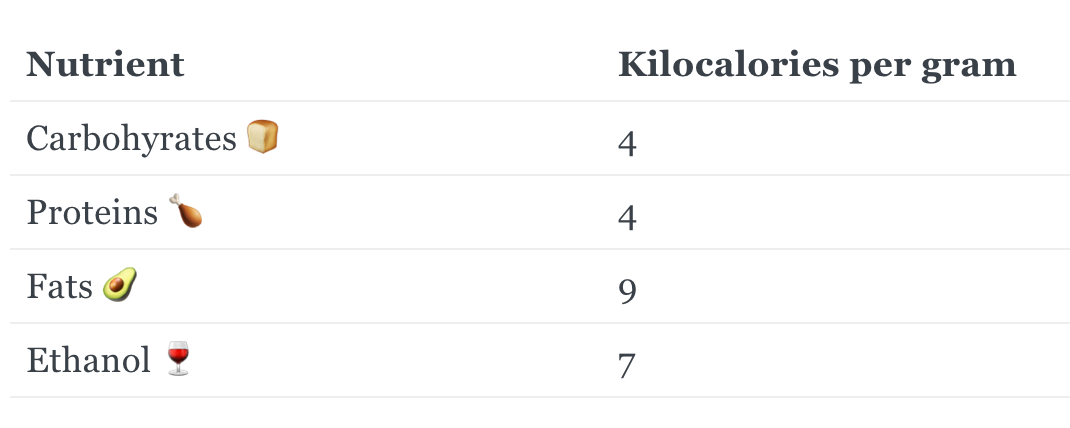

Each compound you consume has a fixed amount of energy per unit mass. Therefore, you can derive your total Calorie consumption by counting macros. (In general, I recommend examining your macros first and then deriving Calories.) The amount of energy per gram of each nutrient is below.

Calories in and calories out will directly affect your bodyweight. If you consume a surplus of energy, you will gain weight. Otherwise, a deficit of energy means that your body taps into its reserves and loses weight.

Weight control is a relatively simple equation. However, don't treat calories as the most important metric. For factors like organ health and body composition, macronutrients matter as well. As an example, suppose you consume a limited number of Calories. All of those Calories come from foods with high saturated fat. You will not become physically fat. However, don't be surprised if your arteries clog due to high cholesterol.

Micronutrients 💊

Besides macronutrients, the human body also requires other compounds in relatively small amounts. These are the micronutrients, and they tend to be measured in milligrams. Due to their small quantities, they are not sources of energy. Instead, micronutrients usually act as catalysts for vital bodily reactions (such as bone growth).

There are two variants of micronutrients:

Vitamins 🍊

Minerals 🧲

Vitamins are organic compounds while minerals are inorganic. That's about the only main difference between the variants. In general, a balanced diet should cover all the necessary micronutrients.

Actionable Eating 🥦

Every human is different, so there's no one formula for eating. There are a few common traits we all share, however. The human body resembles a system striving to keep equilibrium. Thus any changes you make must stay consistent. Doing a diet may have some results in the short term, but as soon as you revert to old habits, your body follows suit. Your body will converge to match your actions.

To start off, set your desired trajectory. Your strategy should reflect your goals. It wouldn't make sense to tell a person trying to lose weight to have the same diet as a person trying to gain muscle. Notice that there are plenty of valid reasons to plan out how you eat:

You'd like to lose weight.

You'd like to lower your bodyfat percentage.

You'd like to get stronger or gain muscle.

You want to maximize your lifespan.

Figure out what you want first.

Running the Numbers

Human bodies vary a lot, so your caloric and nutritional needs may not be the same as mine. You'll need to establish some sort of baseline for yourself first. The two main baselines are basal metabolic rate (BMR) and total daily energy expenditure (TDEE).

Your BMR represents how many Calories the body burns just by living. Males and people with larger bodyweights will have a larger BMR. Your TDEE approximates how many total Calories you spend daily based on your BMR and activity level. (Generally, TDEE is more useful than BMR.) So if the number of Calories you eat in a day matches your TDEE, you should maintain the same weight. There are many TDEE calculators on the Internet. Pick your favorite and determine your TDEE.

With your TDEE in hand, add or subtract 100-200 calories, depending on if you're looking to gain or lose weight. Having a larger difference may cause unwanted side effects (such as muscle loss or fat gain). Note that over time, you'll want to periodically recalculate your TDEE. It will change if your weight changes. You now have your daily target Calories.

Next up, you'll want to calculate your macronutrient targets. It's best to start with protein. Aim to consume 0.7-0.8 grams of protein per pound of bodyweight. (You should also be able to derive your daily Calories from protein.) Around half of your daily Calories should come from carbohydrates. The remaining Calories in your "budget" will go towards fats. If you're looking to lose fat, it may be worth reducing your carbohydrate ratio and replacing it with protein.

At this point, you should know how many grams (and Calories) of each macronutrient to consume each day. Find the foods that will bring you to that target and enjoy! Prefer complex carbs over simple carbs and try to limit saturated fats.

Miscellaneous Questions

Below are some related topics that did not fit particularly well in any of the prior sections.

How do I find foods that will hit my macronutrient targets?

It may be helpful to think of eating foods as a system of equations. You cannot control the macronutrient ratio of foods, but you can how much you eat. A serving size on a nutrition label is arbitrary; you should decide the portion that's right for you.

Usually, the "cleaner" the food, the simpler it is in terms of macronutrient balance. They also tend not to have too much saturated fats or simple carbs. For example, wheat bread contains mostly carbs while chicken breast is mostly protein. Something like fried chicken will have weird ratios (and high saturated fat), making your calculations much harder.

What if I feel too hungry or too full?

Empty calories keep you hungry, forming a vicious cycle. Usually, cleaner foods should a lower number of Calories per unit volume. Therefore, it's easier to feel satiated if you're eating a high volume of clean foods.

Consider doing the opposite if you're feeling too full. Consuming liquids (e.g. a protein shake) also tends to prevent people from feeling full.

Do I really need to count calories? Isn't this overkill?

The proper answer is that it depends on your goals. If you're looking to win a bodybuilding competition, you should probably track numbers. If you generally want to get into better shape, it's not necessary at all. You should be able to learn to approximate things quite well without wasting much time. It's harder if you're eating at a restaurant, but don't worry too much. Your systematic habits will determine long term results.