Understanding your Equity Compensation

When I joined my first startup, options were the most confusing part of my compensation package. Here's what I learned.

When I joined my first startup, options were the most confusing part of my compensation package. Nowadays it's pretty common for a decent chunk of a tech worker's compensation to be paid as equity in the company. However, the value, laws, and strategy about handling equity tend to be more complicated than it seems on the surface.

Part 1: RSUs (The Easy Stuff)

If you find yourself working at a public company or a large startup, equity compensation will likely be given as restricted stock units (RSUs). A standard equity package would grant an employee a given quantity of RSUs over an extended period of time (usually 4 years) in addition to normal salary compensation. RSUs share the same properties of normal company stocks, however the employee can be subject to a cliff and a vesting schedule.

To incentivize employees from leaving a company too early, equity packages can include a cliff, which is a clause stating that the employee must remain at the company for a certain amount of time before any RSUs get paid. Cliffs typically last about one year. If you were to leave from the company before the cliff for any reason, you would receive no equity.

During the span of employment, the equity will otherwise vest over time, meaning the employee has earned the equity. Equity typically vests once per month, except for cases where an employee has not passed the cliff. In such a case, nothing vests until the cliff passes, but once the employee has reached the cliff, the entire year's worth of equity will all vest at once. For most companies, equity vests at a uniform rate. Each month or so, you'll receive the same number of shares. However, there are some companies (such as Snapchat or Amazon) that have back-loaded vesting schedules. They want to incentivize employees into staying for the entire duration of the equity package.

Calculating Total Compensation

To run through a concrete example, suppose we work for a large public company. Let's call this large public company Foogle. You receive an equity package of 240 RSUs over four years with a one year cliff and monthly vesting as part of your offer from Foogle. For the first year, you receive no stocks until your first anniversary at the company because of the one year cliff. However, upon hitting the cliff, you'll receive the entire year's worth of 60 RSUs at once. Following the cliff, each month awarded you with 5 additional RSUs. By the end of the four years, you will have received 240 RSUs in total.

Because the value of equity can be quite high compared to a normal salary, it's usually wise to think in terms of total compensations rather than just what a company pays in cash. Continuing off the previous example with Foogle, suppose the offer had an annual salary of $100,000 and the value of a single share of Foogle is $1000. Since you receive 60 shares of stock per year, your total compensation would be $160,000 per year. (After four years, assuming no changes in compensation, your annual total compensation would then drop to $100,000.)

Factors to Consider

Additional factors to consider when receiving RSUs include the liquidity and volatility of your stock. Those working for public companies should not have any issues with liquidity: they're free to sell their stock as soon as it vests. On the other hand, those who own startup stock have to wait for a liquidity event, such as an IPO, before cashing out. For example, at the time of writing this post, employees at Airbnb cannot liquidate their Airbnb stock. Soon that should change, because Airbnb is scheduled to go public in the near future.

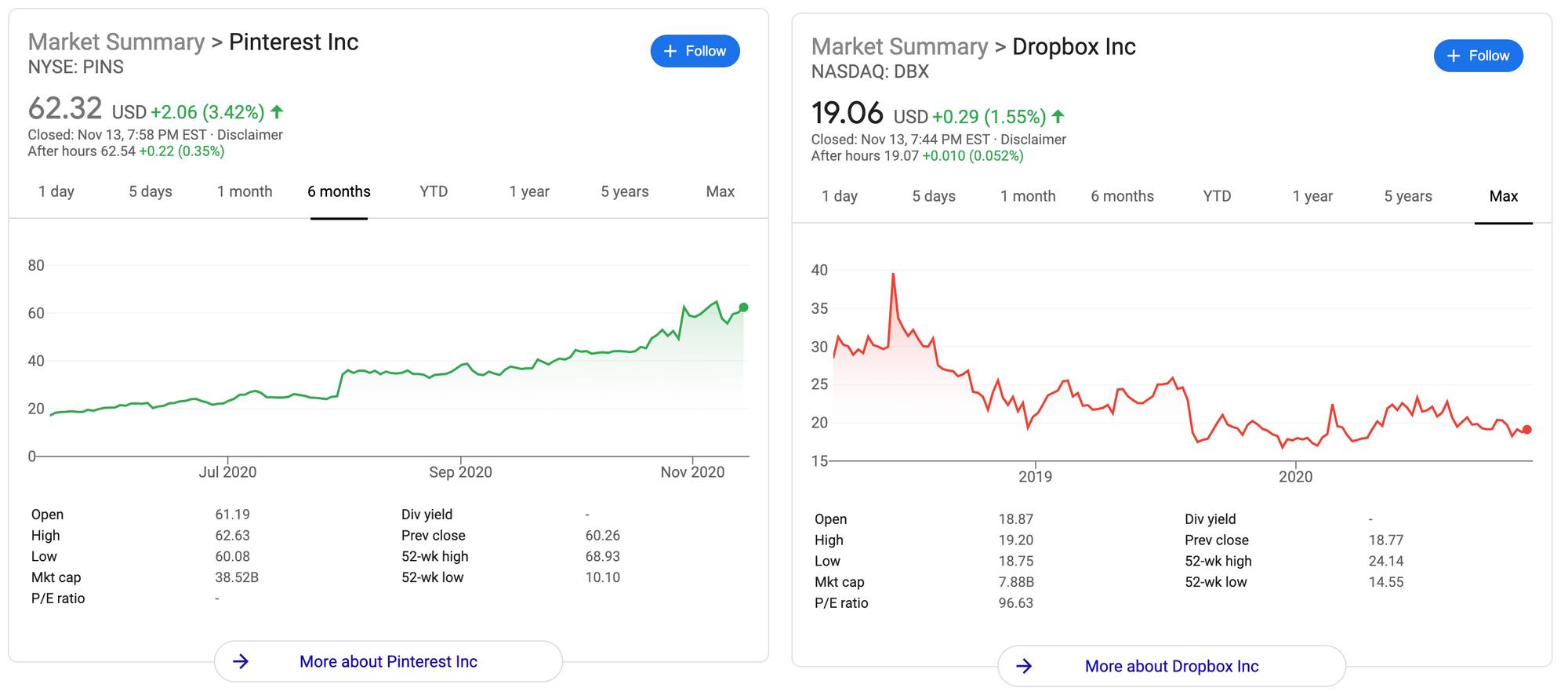

In general, equity also shifts in value over time. Should the valuation of Foogle double over the year, your annual total compensation suddenly jumps to $220,000. On the other hand, your prospects won't look as good should the stock price tank. Both situations are quite common in the real world. Pinterest stock prices have tripled within the past few months, while Dropbox stocks have been steadily declining in value ever since its IPO.

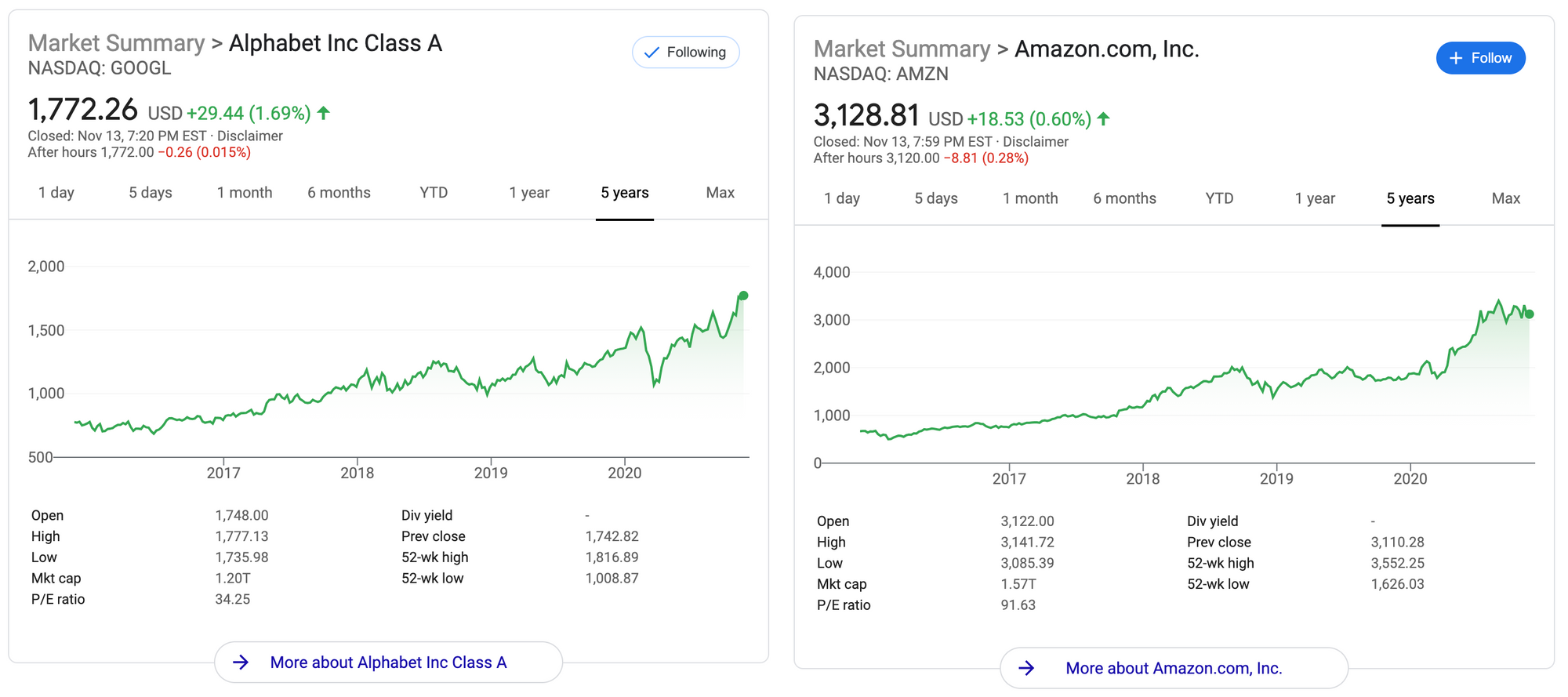

Depending on your risk tolerance, personal needs, and belief in the future of the company, it may sometimes be wiser to immediately sell off your vested equity and use the cash to create a more diversified portfolio. As an amusing anecdote, back in my days of working for Google, it wasn't uncommon to hear of fellow engineers automatically liquidating any vested Google stock and immediately putting the money into Amazon stock. They didn't get the memo about diversifying their portfolio, but swapping GOOG for AMZN wasn't a bad strategy in hindsight.

Part 2: Options (The Tricky Stuff)

If you find yourself working at a smaller startup, equity compensation will likely be in incentive stock options (ISOs). An ISO grants the employee rights to buy shares of a company at a fixed price. (Those familiar with options trading may notice that an ISO has many similar properties to a call option.) Like with RSUs, options can have a cliff and vest over time. Unlike RSUs, vesting does not mean you own the stock. You need to exercise your options in order to own actual shares. Additionally, keeping vested options is contingent on staying employed at a company. After leaving a startup, it's standard that any options that are vested but not exercised will expire after 90 days.

To exercise a startup option, you must pay the strike price to convert the option into an actual share of stock. The strike price is usually the fair market value (FMV) of the company at the time your employment begins. The FMV of a share gets updated whenever a startup receives a 409A valuation. Companies are required to get a new 409A valuation every year. Notice that with options, there's now the possibility that the employee loses money. With startup options, employees bet on the company dramatically increasing in value. Therefore, any profits come from the difference between the value of stock when it's sold and the original strike price paid.

Calculating Total Compensation (Again)

As an example, suppose we work at a private startup called Snail AI. You're offered an annual salary of $100,000 and granted an equity package of 80,000 options over the span of four years. The startup has a 409A valuation of $1 billion and conveniently has 1 billion total shares. As a result, the fair market value per share (and your strike price) is exactly a dollar. After a year, you'll vest 20,000 shares that cost $20,000 to exercise. Should you choose to exercise those shares, your total liquid compensation drops to $80,000 because you needed cash from your salary to pay for the exercise. You're unable to sell your shares because the startup is private, so the equity is right now just a piece of paper.

The upside from startup stock comes from the potential for large company growth. Suppose you joined Snail AI in 2020 and stuck around long enough to vest your entire equity package. Four years have passed, and Snail AI is now worth $20 billion in 2024. That's a 20x increase! The fair market value of your 80,000 options (assuming no dilution) is now $1.6 million. It still costs a total of $80,000 to exercise since your strike price doesn't change. Looking back, with the current FMV per share of Snail AI stock, your total compensation is now $480,000. Looks a lot better than the Foogle offer, right? Before you get too excited, note that such high company growth isn't guaranteed (or probable). Since Snail AI has not had an IPO, most of that compensation is "paper money." On paper you've made a lot of money, but you won't be able to touch any of it for a while. (And we haven't even scratched the surface with taxes.)

Why give options? Why give RSUs?

Startups prefer to award options in order to align incentives between employee and employer. In order for the employee to profit, the startup must grow. If the startup fails, the employee gets nothing. Options are also quite lucrative since it's easier for smaller startups to multiply in value over the span of a few years. Finally, options aren't a financial burden on the company. Since an option is just a right to buy shares of company stock, the company actually gains liquidity if an employee exercises.

At a certain point in a company's lifespan, it will start awarding RSUs instead of ISOs. The inflection point tends to be around the time a startup surpasses a valuation of $1 billion. The reason for such a shift is because the cost of exercising options will have become quite expensive. Awarding ISOs would disincentivize new people from joining, since exercising options will now be a financial burden and incur sizeable risk for an individual employee. At the same time, the cost per share of a company has achieved high enough value that awarding shares directly would make for a competitive compensation package. As a result, the appeal of the startup's equity package shifts from the hope of high growth of the stock to high inherent value of the stock. Unfortunately, RSUs do not align incentives as well, since employees benefit even if the company stagnates. However, the shift to RSUs tends to be more of a necessary choice when ISOs lose their appeal.

Alternative Minimum Tax and Golden Handcuffs

Exercising options may incur substantial tax burdens. ISOs are subject to an alternative minimum tax (AMT). The AMT is a means of preventing high income earners from avoiding too much tax. During time of exercising, you technically profit off the spread between the original strike price and the current FMV of the stock options. If your profits off the equity exceed a certain amount, you'll have to pay the alternative minimum tax.

Let's circle back to the example with Snail AI. Suppose that you happily exercise a year's worth of stock options and act all smug about having almost half a million dollars in annual compensation. Because of the AMT, on tax day, you get treated as if the half million were your true income. Your income tax will therefore amount to several tens of thousands of dollars. Remember how much real money you earned? It was around $80,000. You probably can't afford to pay your taxes. Have fun in jail!

When an employee cannot afford to exercise vested options, he or she is in golden handcuffs. There's a lot of money on the table, but now the employee no longer has the option to leave the company, due to the clause where options expire 90 days after leaving the company. Now you're faced with a dilemma: remain at your current company until a liquidation event or surrender a lot of valuable stock. Admittedly golden handcuffs are a nice problem to have. It's a better situation to have compared to working at a startup on the verge of going bankrupt.

Since AMT depends on the spread between the FMV and strike price of shares, it's "cheaper" to exercise options are early as possible. If you truly believe in your startup and have excess cash available, then exercising as soon as options vest may be the way to go. On the other hand, if you value optionality, you don't have the cash, or your startup is going down the dumps, it may be worth holding off before exercising your options. It's also important to note that AMT triggers at a certain threshold. In situations where it's unfeasible to exercise everything, it's still possible to exercise a subset of your shares without accumulating a heavy tax burden.

Part 3: Everything that I Missed

This post is getting long, but we've barely scratched the surface when it comes to startup equity. I've added a list of top-of-mind topics that we've yet to explore. They're in no particular order. Maybe it might be good content for a follow-up post.

- Fundraising and dilution

- Liquidation events, such as an acquisition or IPO

- Secondary markets

- Stock appreciation rights

- Equity refreshers

- ISOs vs NSOs

- Preferred price vs strike price

- Managing expected value, variance, and risk

- When NOT to exercise your options

- Net present value

- Early exercise

- Balancing optionality, liquidity, career, and happiness

In particular, we've really missed discussing the strategy when it comes to vesting and exercising startup options. Decision making in the startup world can get rather spicy.

I'll also take the opportunity to share some disclaimers. This blog post has touched upon money, taxes, jail, and career choices. I am not a tax professional, and I'm definitely not your mom. Please consult the relevant parties instead when making key life decisions. Also, treat this blog post as an opinion piece. At the end of the day, you need to think for yourself.

Happy investing!

Comments ()